But the honor bestowed on the legendary singer transcends her contribution to Latin music and recognition for acclaimed Hispanics, solidifying our culture and influence in America.

Celia Cruz’ Barbie doll symbolizes much more than the legendary performer putting the music genre on the map. Although she passed in 2003, 20 years later, she’s still seen as a beacon of hope and a staunch advocate for freedom, especially in historically challenging times.

Mattel’s Inspiring Women series inclusion of the Celia Cruz doll reflects the Cuban icon’s legacy and stronghold on Latin music. They’ve struck commerce gold with the Barbie doll. No longer available on the toy retailer’s website and perpetual backorder, the Celia Cruz Barbie is in high demand and sold out from other popular retailers. Walmart has it. But it’ll cost you. Almost double, in fact (original Mattel price: $35). My partner recently purchased it as I’ve admired the singer all my life and we share the same heritage.

So, what does the Celia Cruz Barbie look like?

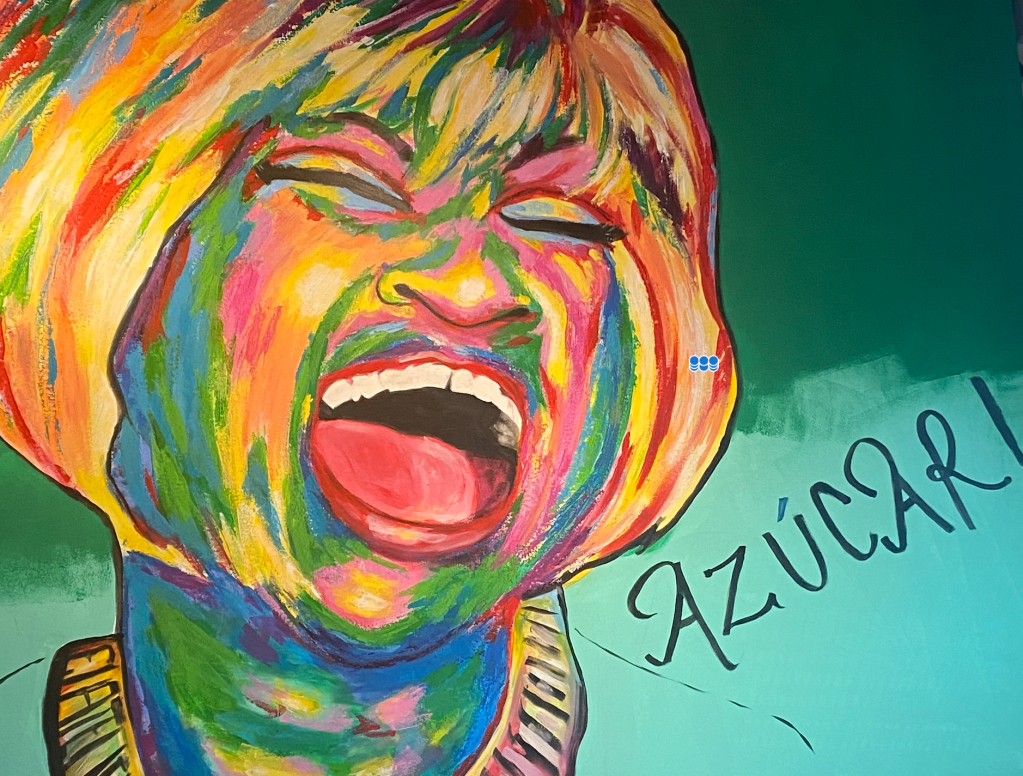

Known for her dazzling, colorful outfits and elegant wigs on stage, Mattel recreates the singer’s signature look with an eye-popping red and gold dress, matching gold block-heeled sandals, and pristine blonde wig, complete with a gold microphone in hand and images of the performer in the sixties and seventies throughout the box seal the packaging’s aesthetic.

Celia Cruz, born 1925 in Barrios Suarez, Havana, Cuba, was one of four children. Lover of music and dance from an early age, she acquired her first pair of shoes by performing for a tourist in Cuba. From then on, Celia’s passion for singing led her to perform in school productions, notably Havana’s National Conservatory of Music. Her talent caught the attention of musicians and producers after winning a radio contest called the “Tea Hour.” She joined the Las Mulatas Del Fuego group and became the first female lead singer of La Sonora Matancera, Cuba’s most famous orchestra.

On the heels of her success with the orchestra and while touring in Mexico, Cruz decided not to return to Cuba as the Cuban Revolution was in full swing in 1960. Enraged at Celia’s defection and realizing he had lost one of the country’s national treasures, the vindictive dictator banned the singer from returning to the island. And she never did. She made America her permanent home and joined the Tito Puente orchestra in the mid-1960s. Cruz’s dazzling costumes, high-energy performances, and magnetic personality catapulted the group’s popularity. The label (Fania) dedicated to salsa, a sound mixing Cuban and Afro-Latin beats, emerged in the late 1960s and 1970s when she recorded one of her trademark hits, “Quimbera.” Unfazed by being the only female performer in a large band (unheard of at the time in the male-dominated industry), Celia’s fame continued to ascend — touring internationally and performing with the biggest names in music.

The multi-Grammy-award-winning celebrated songstress’s career spans six decades with 80 albums, earning 23 Gold Records. She pioneered the music genre of salsa globally, paved the way for other artists, and amplified her Afro-Latinidad heritage through song, dance, and dress. Mattel creating a doll in her honor is an incredible source of pride for me and countless Latinos, further establishing her star power and legacy. Check out Mattel’s website to buy the Celia Cruz Barbie and other dolls from their Inspiring Women Series.